Tip: Activate javascript to be able to use all functions of our website

Many children in Burkina Faso suffer from malnutrition in the first years of their lives. Yet proper nutrition is never as important as at the beginning of life. In this project in Burkina Faso’s south-western province of loba, young mothers receive transfer payments and training. The goal: reduce malnutrition in newborns and young children, thereby setting a positive course for the future in the long term. The evaluation analyses the long-term impacts of these payments on mothers, children and the village communities.

Burkina Faso is one of the poorest countries in the world: the Human Development Index (HDI) ranks the country 182 out of 189 nations. Intensified by climate change, regular droughts and land degradation pose significant challenges to the food security of the growing population. This applies in particular to rural areas and to pregnant women and small children. Particularly for children, nutrition is crucial in the first 1,000 days of life. Malnutrition and undernourishment have a massive impact on children’s cognitive development and physical health. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 25 % of children under five in Burkina Faso suffer from impairments to their growth.

The project aims to improve the food security of as many as 15,000 mothers and mothers-to-be and their 18,000 infants in the province of Ioba in south-western Burkina Faso. The women receive quarterly payments for three years. Mothers of children under the age of two and mothers-to-be are eligible to participate. To ensure reliable transfers via mobile money, the women receive assistance to apply for ID cards and are provided with a mobile phone. These aspects include women financially and empower them to assert their economic and political rights. Mothers-to-be are also invited to participate in educational campaigns about nutrition, hygiene and health. The campaigns are conducted in local women’s groups, but also presented in movies or theatre performances and on the radio.

The project primarily focuses on participating women and their children, but also on their communities and local economies. The primary goal of the impact evaluation is to capture the – expected and unexpected – causal impacts. To this end, both qualitative and quantitative data is collected at the level of the women, their children, communities, markets and health centres. The data are collected before the start of the project (baseline), one year later and three years later. The analyses provide reliable findings for possibly expanding the project to other regions. It allows to answer the following questions: did the payments reach the women, and did the targeting criteria actually work? What have the women learned about food security and nutritional practices, and how does this affect their behaviour? Has participating in the project changed the physical and mental health of the women and children – for example, have growth impairments among children been prevented? How has the project been received by families and communities, and how does it affect domestic violence and neighbourhood conflicts? Have there been negative impacts – for example on food prices – due to changes in demand patterns? Do impacts that are visible in the short term still persist after three years?

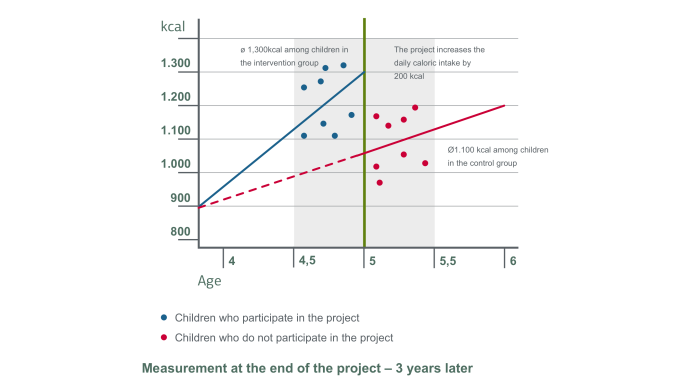

A “regression discontinuity approach” is used to answer all these questions.

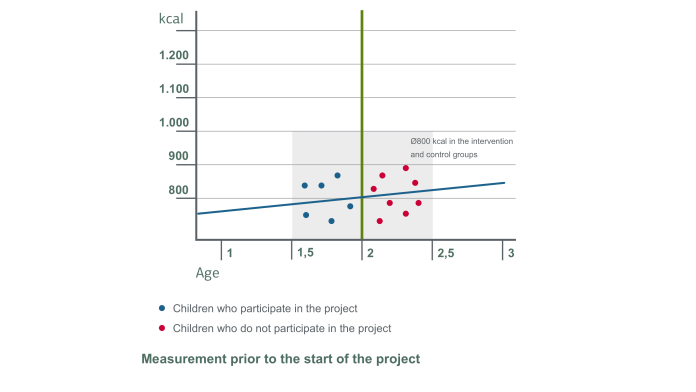

Let’s assume before the start of the project, the average caloric intake of children aged one to three years is 800 kcal (kilocalories). Households with children under two years of age now receive transfer payments, while households with children over two years of age do not. This clear targeting criterion can be used to identify the payments’ impacts. It is assumed that mothers and their children between the ages of one and a half and two can be compared to children between the ages of two and two and a half. The households are surveyed before the project begins in order to obtain initial baseline information about these children and the households.

At the end of the project, the children are three years older. This means that mothers and their children aged four and a half to five years are compared with mothers and their children aged five to five and a half years. The households are surveyed again to collect this data. Taking into account the results of the previous baseline survey, the impact of the measure can now be calculated in the fictitious example as follows: the children’s caloric intake increases with age and is 1,100 kcal for children in the comparison group. For children participating in the project, the value also increases, but to 1,300 kcal. This is 200 kcal, or about 18 % more than for children who are not part of the project.